To date, no complete evolutionary explanation has been given for the formation of the human species, and certainly not a complete and unifying explanation at the same time.

An evolutionary explanation explains a physiological or behavioral phenomenon in a species and is complete when it includes a description of adaptability to a defined ecological change. A unifying explanation explains several phenomena as a result of a single reason, as, for example, a description of many geological phenomena as a result of the displacement of tectonic plates (displacement of continents).

In a series of four scientific articles published at the end of 2020 and throughout 2021, all of them together with my partner at Tel Aviv University, Prof. Ran Barkai, we laid out the basis for the explanation and the complete and unifying evolutionary explanation for the formation of the human lineage leading to the Homo sapiens species. We explained many of the significant phenomena in human prehistory, such as increased brain volume, language development, changes in stone tools, and more.

The purpose of the post is to present a concise description of the explanation.

In the first three articles [1,2, and 3 with Raphael Sirtoli], we have set the background to two basic assumptions on which the unified explanation is based:

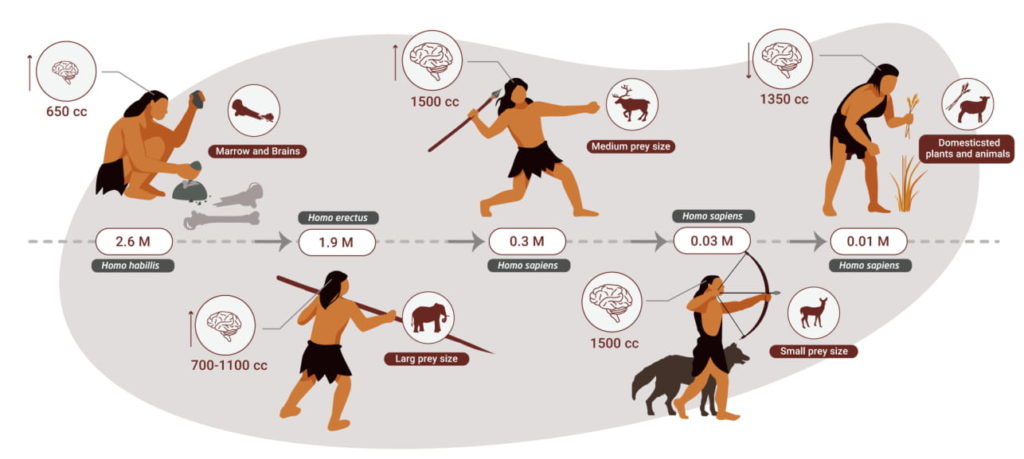

1. Humans specialized in hunting large animals. [1,2]

2. Humans were hyper-carnivores that consumed over 70% of their diet from animals for most of the Stone Age (between 2.6 million years ago and about 11,000 years ago) [3].

Establishing these assumptions allowed us to argue that mitigating the bioenergetic effects of the need to obtain smaller animals in the face of the extinction of large animals during the Stone Age was the unifying ecological factor for many of the physiological and cultural adaptations that humans underwent during the Stone Age [4].

The first and second articles are intended to present the hypothesis that humans evolved as large animal hunters. Both also deal with two critical biases in research that have to date prevented the recognition of large animals’ importance and the criticality of hunting in ancient human economics.

We listed four reasons that have led humans to specialize in hunting large animals as a source of animal food:

1. Large animals constituted the majority of the prey animal biomass in the human environment.

2. Large animals do not escape and can be hunted with uncomplicated tools

3. The energetic return for hunting larger animals is higher than that of smaller animals.

4. Large animals have a relatively higher fat content, decreasing at a slower rate during scarcity periods. Fat was essential because human protein intake was physiologically limited.

The two biases that have to this day prevented the recognition of the importance of large animals, and the importance of hunting in the ancient human economy are:

1. A smaller portion of large animal bones was brought to central campsites, and therefore their representation in the archaeological record is skewed downward. [1]

2. 20th-century hunter-gatherers, on which research has so far been based, are not a suitable source for reconstructing the relative amount of plants compared to animals in the diet of ancient humans. [2]

The first article discusses the underrepresentation of large animal bones in archeological sites. The paper analyses an actual case of recent hunter-gatherers’ (the Hadza) hunting record. In the actualistic case study, the number and size of the animals are known, as well as the number of bones brought to the central camp. The article shows that the relation between the size of the animal and the number of bones brought was negative. The largest animal in the collection, the giraffe, contributed 57% of the calories. Still, only 7% of the bones on the site belonged to it.

The second article deals with the “mother of all evils” of the reconstruction attempts of the human trophic level, i.e., what percentage of the calories were provided by plants and animals. There is no reconstruction in the literature that does not rely on 20th-century hunter-gatherers and accordingly presents a flexible trophic level based on local ecological conditions. An analogy to 20th-century hunter-gatherers was an accessible source for researchers who tried to quantitatively reconstruct plants and animals share in the diet. The overarching reliance on 20th-century hunter-gatherers is understandable, as archaeologists and paleoanthropologists were tasked with the job. Still, frustratingly, the archaeological record, apart from stable isotopes, simply doesn’t have the data that can directly answer the question. The article describes the considerable difference between the ecology during most of the Paleolithic era, as evidenced by several species of elephants and other large animals in archaeological sites, and present ecology. The few large animals that survived extinction are limited to game reserves. The article also details the implications of the technological difference in the management of stone tools economics compared to the metal tools in use today that are received in a trade with neighboring farmers and herders. In summary, this article concludes that contemporary hunter-gatherers may be somewhat appropriate as an analogy to the end of the Stone Age when most large animals were already extinct; The dog is domesticated, and the bow was developed as a hunting tool. They are certainly not suitable as analogs for earlier periods, constituting about 99% of the Stone Age.

The third article [3] was written, together with the biologist Raphael Sirtoli, to reconstruct the relative share of plants and animals in ancient humans’ diet without relying on 20th-century hunter-gatherers. For the first time, in this paper, we have presented a broad paleobiological approach as a source of evidence. Fifteen different lines of evidence from the field of human biology, including metabolism, genetics, and internal and external morphology, present a picture of humans as adapted to high consumption of animal foods. Some evidence showed that humans underwent adaptations to animal food consumption, which prevented them from efficient utilization of plant food, a recognized sign of a specialized species’ evolution. Some of the paleobiological evidence could be interpreted as an adaptation to the consumption of large animals. To the fifteen biological pieces of evidence, we added ten lines of evidence from additional areas of knowledge: archeology, paleontology, ethnography, and zoology. Most of them also supported the conclusion that humans were hyper-carnivores of large prey animals.

Having established the two basic assumptions above, that humans specialized in hunting large animals and that most of his diet came from animals, we could present the complete and unifying explanation for human evolution. We could then argue that declining prey animal size was a critical source of ecological pressure for humans.

Just as in economics, the best way to understand human behavior is to follow the money; in evolution, the best way to understand the reason for the change is to follow energy, the “currency of life.”

The extinction of the large prey animals created a deficit in humans’ energetic budget. There is a higher energy cost to obtaining eighty fallow deer instead of one extinct elephant. Thus, in humans, adaptation following ecological change was saving energy while hunting smaller animals.

This basic approach led us to explain the significant developments in human evolution as repeated adaptations to energy savings while hunting animals, which shrink in size [4]. The adaptations we explained in this way are:

1. The increase in human brain volume after Homo erectus

2. The appearance of spoken language

3. The evolution of Homo sapiens, including the multitude of morphological, physiological characteristics

4. Changes in stone tools and hunting techniques

5. Increasing consumption of plant food towards the end of the Stone Age

6. The extinction of the Neanderthals

7. Domestication of the dog

8. The decrease in the size of the human brain at the end of the Stone Age

9. Domestication of plants and animals and the transition to agriculture.

To the keen eye among the veteran readers, the thought process described above will sound familiar. Some, if not most of these insights, have already appeared in our 2011 article Man the Fat Hunter [5]. Today, about nine years after the article appeared, I completed a task I had set myself then – to test and expand the hypotheses raised in the 2011 article.

The next task is to fully describe the outline presented here in a book. But before that, I will try to publish one more article that will offer a hypothesis for the unifying factor of the ongoing extinction of the large animals at different times and places on earth during the Stone Age. Yes, you guessed it, humans are the main suspects. According to the data we collected, their preference for hunting large animals and their critical need for fat led them to pursue precisely those animals and those age groups that were most susceptible to extinction. In short, humans cut the branch on which they were sitting. Just as we do today.

Stay healthy

Miki

References

- Ben-Dor M, Barkai R. Supersize does matter: The importance of large prey in Paleolithic subsistence and a method for measurement of its significance in zooarchaeological assemblages. In: Konidaris G, Barkai R, Tourloukis V, Harvati K, editors. Human-elephant interactions: from past to present: Tübingen University Press; In press.

- Ben-Dor M, Barkai R. The importance of large prey animals during the Pleistocene and the implications of their extinction on the use of dietary ethnographic analogies. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 2020;59:101192.

- Ben-Dor M, Sirtoli R, Barkai R. The evolution of the human trophic level during the Pleistocene. Yb Phys Anthrop. 2021.

- Ben-Dor M, Barkai R. Prey Size Decline as a Unifying Ecological Selecting Agent in Pleistocene Human Evolution. Quaternary. 2021;4(1):7.

- Ben-Dor M, Gopher A, Hershkovitz I, Barkai R. Man the fat hunter: The demise of Homo erectus and the emergence of a new hominin lineage in the Middle Pleistocene (ca. 400 kyr) Levant. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e28689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028689

I am a Ph.D. in archaeology, affiliated with the department of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University. I research the connection between human evolution and nutrition throughout human prehistory.

I am a Ph.D. in archaeology, affiliated with the department of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University. I research the connection between human evolution and nutrition throughout human prehistory.